Even though Elon Musk remains convinced that the future of the human race lies in the stars, and we continue to destroy our home planet, there are also questions about whether we're alone out here.

Up there with the most prominent conspiracy theories, we seem to be obsessed with outer space and whether the government is hiding things from us.

The shadowy Area 51 is a conspiracy theory all on its own, but alongside some people still thinking we faked the Moon landing, others are convinced the 3I/ATLAS comet is a secret alien mothership.

Various 'experts' have spoken out on alien life, with some even suggesting that we found life on Mars years ago but accidentally killed it.

Advert

Given that there are fears about how our first contact with aliens would actually go down, they likely won't be the friendly little fellows we met in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

In the aftermath of one NASA scientist giving his theory on 'radical mundanity' as why we haven't been communicating with aliens, a group of researchers from ETH Zurich has put forward another idea – as published in Nature Astronomy.

Speaking to the Daily Mail, lead author Dr. Craig Walton says we're simply looking in the wrong place. Apparently, a search for life on water-rich planets is a waste of time. Instead, we should be turning our telescopes to those that are bountiful in phosphorus and nitrogen.

Even if a planet is abundant in water, we need phosphorus to form the DNA and RNA that store and transmit our genetic information, while nitrogen is essential in creating the proteins that are the basic building blocks of our cells.

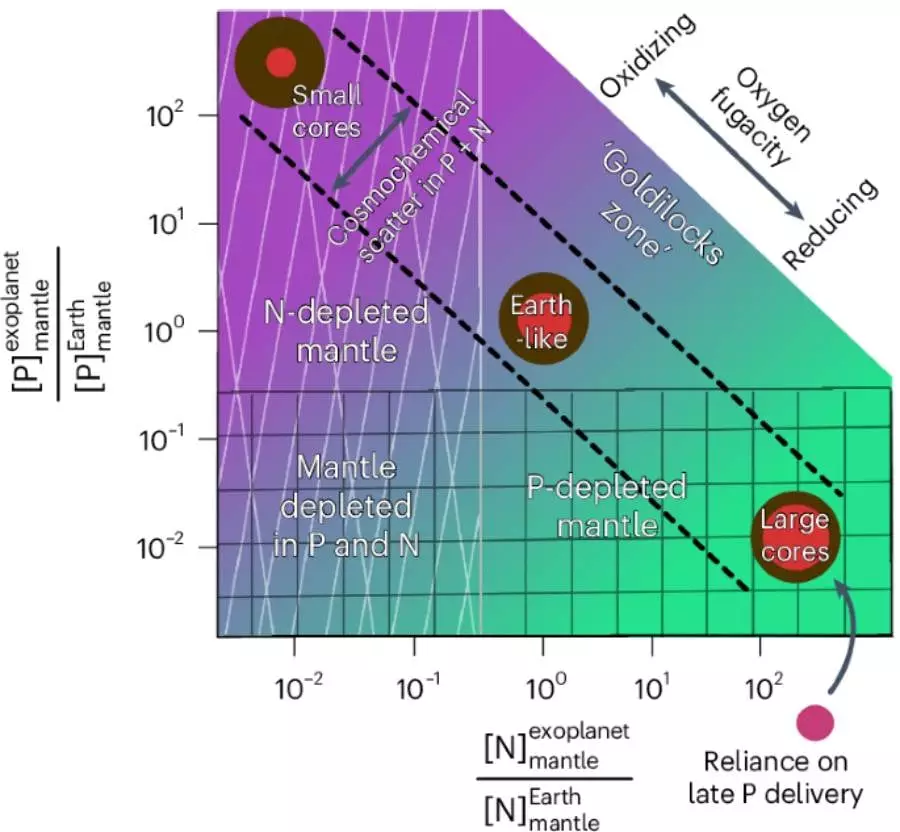

This means finding planets in a so-called 'chemical Goldilocks zone' is even harder than you might think.

As Walton explained: "You could feasibly have a planet that looks great with oceans and even dry land, but there is no life and never will be because the other elements you need are simply all but absent."

Even though liquid water and oxygen are essential to survival, we should be focusing on a planet's 'oxygen balance' at the moment of formation. This is what determines how much phosphorus and nitrogen will be left for potential lifeforms.

When planets cool, heavy elements sink while the lighter ones float upward to form the mantle and crust. If there's too much oxygen, phosphorus is trapped in the mantle and nitrogen is forced out into the atmosphere.

Too little oxygen means phosphorus is bound to heavy elements like iron and pulled down into the core.

Looping back to the Goldilocks idea, Walton added: "Having too much or too little oxygen in the planet as a whole – not in the atmosphere per se – makes the planet unsuitable for life because it traps key nutrients for life in the core.

"A different oxygen balance means you have nothing to work with left at the surface when the planet cools and you form rocks."

There is supposedly a very narrow band where there's just the right cocktail of phosphorus and nitrogen exists in the mantle. Ultimately, Walton claims there could be as few as 1% as many habitable planets as experts previously thought.

Warning that future space exploration shouldn't prioritize oxygen-rich planets when searching for life, Walton concluded: "It would be very disappointing to travel all the way to such a planet to colonise it and find there is no phosphorus for growing food.

"We'd better try to check the formation conditions of the planet first, much like ensuring your dinner was cooked properly before you go ahead and eat it."

Sadly, Walton concludes that Mars is just outside of that lucrative Goldilocks zone and probably isn't the petri dish of life many have pitched it as.