Our eyes and sense of sight are one of the most vital tools at our disposal as humans, yet what we actually perceive could be as far away as 15 seconds into the past according to a mind-blowing new study.

The human body is understandably complex and there are many processes that we go through every single day that scientists still struggle to explain how they actually work.

While you'd be forgiven for thinking that your eyes provide a simple vector for your brain to receive information in front of you, the reality of how our vision works is actually far more complex.

You might already be aware that the lens inside your eye projects an 'inverted' image onto your retina, but what you end up actually seeing is more likely an amalgamation of past images in order to create a sense of stability in your vision.

How are we seeing things in the past?

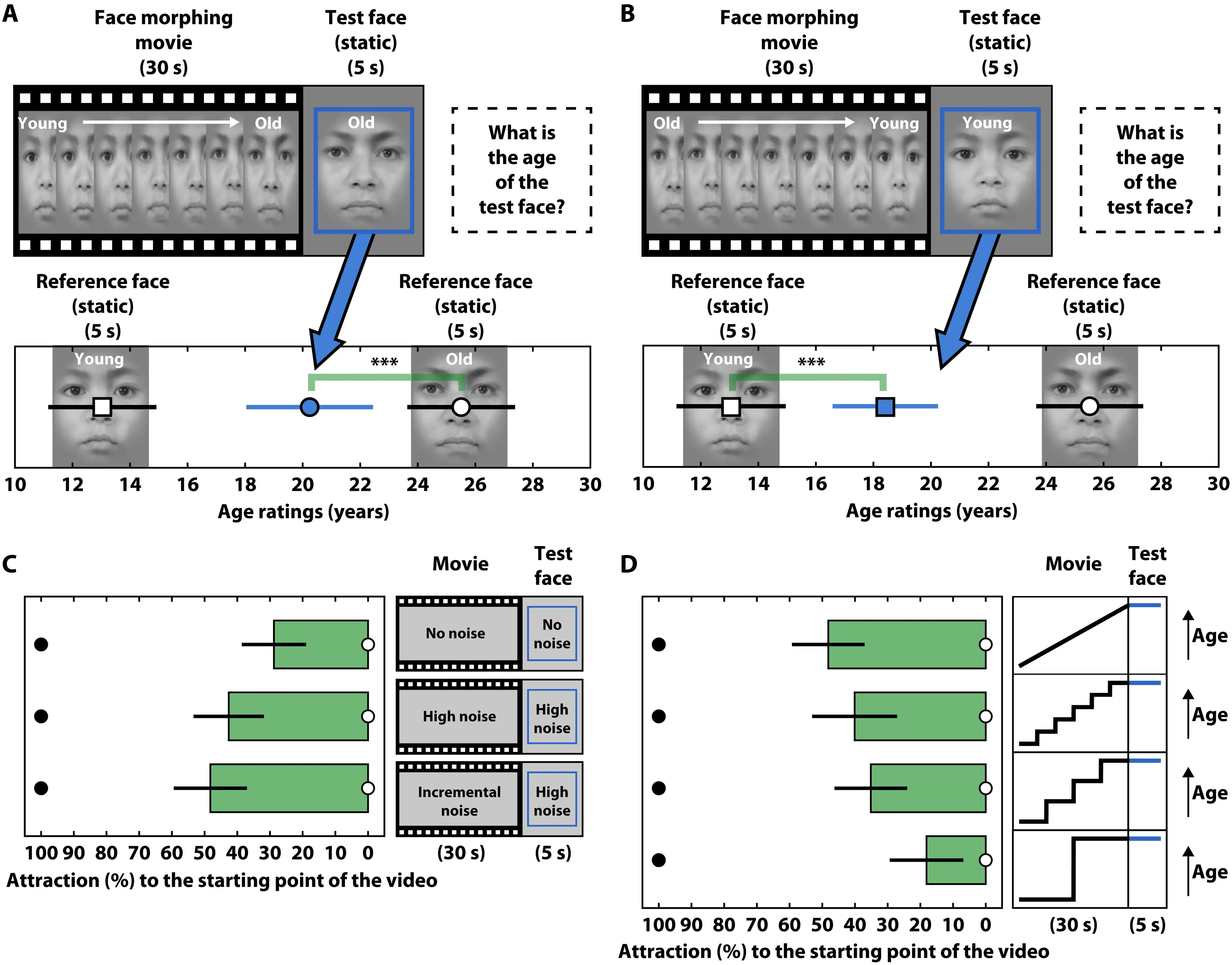

As reported by Popular Mechanics, a 2022 study in the Science Advances journal suggests that everything that we perceive through our eyes is a collection of past 'images' processed by our brain in order to create a steady and stable view of the world.

Advert

"Despite a noisy and ever-changing visual world, our perceptual experience seems remarkably stable over time. How does our visual system achieve this apparent stability?" the study questions.

What scientists have proposed is a 'previously unknown visual illusion' triggered by the brain to make what should be (and is in reality) a far more jittery and visually cluttered sense of vision appear clean through our eyes.

"A continuously seen physically changing object can be misperceived as unchanging," the study outlines, suggesting that the brain could be pulling and merging data from as far back as 15 seconds ago in order to provide something that we can understand.

"We propose that, because of an underlying active mechanism of serial dependence, the representation of the object is continuously merged over time, and the consequence is an illusory stability in which object appearance is biased towards the past."

Think of how you would focus on a moving object far away. When you're looking at it it remains clear in your vision, even though it's not static, and you could even move your own head and keep it relatively in view.

What the study proposes is that this is possible thanks to your brain pulling data from the past of what the object 'should' look like and essentially playing a trick on you.

This causes objects to appear as if they are not changing over time when in actuality they are, and the study itself represents a mind-blowing breakthrough in how we understand not only our eyes and vision, but also how they interact with our cognitive functions.