Archaeologists have uncovered a chilling find inside a ‘Blood Cave’ that was once used for Mayan rituals.

The discovery has unlocked more answers about the ancient civilization after a team of researchers found hundreds of human bones.

The remains were uncovered in an underground cave in Guatemala and could indicate that terrifying human sacrifices once took place there.

The ‘Blood Cave’ is also known as Cueva de Sangre and is buried beneath the Dos Pilas archaeological site located in Petén, Guatemala.

Advert

This cave along with over a dozen more were used by the Maya between the years 400 BCE and 250 CE.

The bones were originally found during a survey of the region in the 1990s but new research into it has uncovered more information on what took place.

Evidence from the remains show signs of traumatic injuries around the time of death.

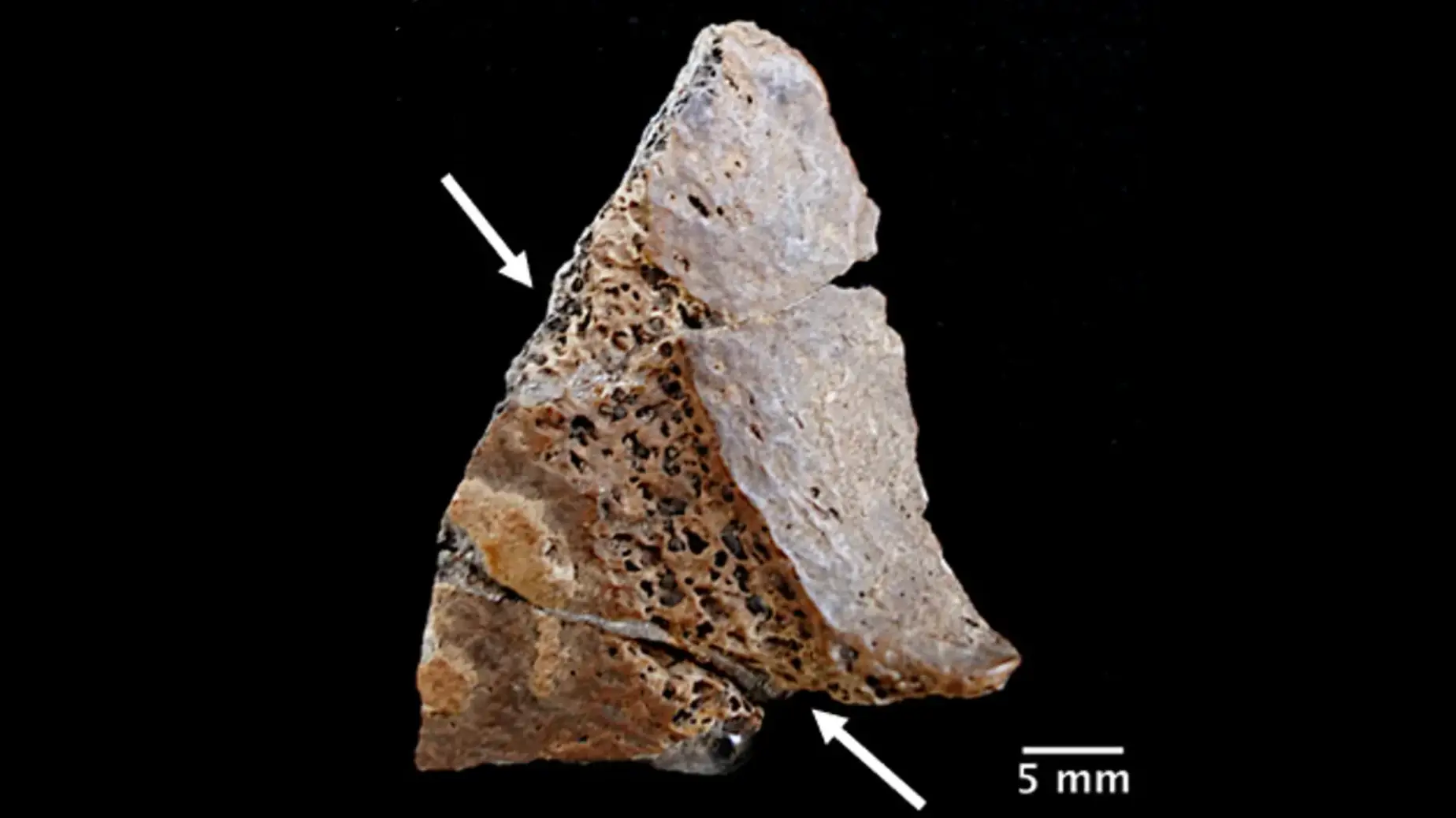

This includes a fragment of a skull and a piece of a child’s hip bone that both appear to have the marks of being struck by a hatchet-like tool.

Speaking to Live Science, Ellen Fricano, who is a forensic anthropologist at Western University of Health Sciences in California, said: “There are a few lines of evidence that we used to determine that this was more likely a ritual site than not.”

This includes the fact that the bones were laid on the surface of the cave rather than having been buried and the bones appear to have been injured as a result of a ritual dismemberment.

Michele Bleuze, who is a bioarchaeologist at California State University added: “The emerging pattern that we're seeing is that there are body parts and not bodies.

“In Maya ritual, body parts are just as valuable as the whole body.”

The Maya civilization were known to practice human sacrifice as religious offerings to gods, particularly during times of crisis.

They believed that doing so would nourish the gods and would ensure the well-being of their community.

With this exciting breakthrough of the bones at the ‘Blood Caves’, researchers are now planning to investigate further by analyzing the DNA of the bones to find out more about who they were.

Bleuze went on to say: “Right now, our focus is who are these people deposited here, because they're treated completely differently than the majority of the population.”

More tests will take place including stable isotope analyses which could have the ability to obtain data about the diets and migration patterns of the deceased.