Wallace and Gromit lied to us, and we're sorry to report that, no, the Moon isn't made of cheese. Still, with SpaceX and NASA working hard at getting humans back on that rocky landscape for the first time since 1972, it looks like we're only scraping the surface of the Moon's mysteries.

While Eugene Cernan had the honor of being the 'last' man on the Moon, the decades since he stood there have left scientists with plenty of time to dig a little deeper into what's going on up there.

As well as confirmation that there were once volcanoes on the dark side of the Moon, and although it's geologically 'dead', this previously undiscovered side of the Moon has become a fascinating point of contention since China's Chang’e-4 lander first rolled there in 2018.

Jumping forward to 2025, China’s Chang’e-6 mission is the first sample return mission and has delivered a fascinating discovery of a rare and valuable meteorite that could have major implications.

Advert

ScienceAlert reports that Chang’e-6 found fragments of carbonaceous chondrite (CI chondrite), which are said to belong to a water-bearing meteorite. What makes this discovery more important is that they rarely survive the journey through Earth's atmosphere.

Marking the first time we've ever observed CI chondrite on the Moon, it suggests volatile-rich asteroids that are 20% made up of hydrated minerals have landed on the surface of the Moon.

The Chinese Academy of Sciences reminds us that under 1% of meteorites that come to Earth are CI chondrites.

Writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal, the researchers said: "Given the rarity of CI chondrites in Earth’s meteorite collection, our integrated methodology for identifying exogenous materials in lunar and potentially other returned samples offers a valuable tool for reassessing chondrite proportions in the inner solar system."

Chang'e-6's samples come from a crash site on the South Pole-Aitken Basin, which is one of the biggest impact craters in the solar system.

Considering the Moon doesn't have an atmosphere to burn up meteorites, the velocity at which objects collide with it means we'd expect them to vaporize or be tossed back into space.

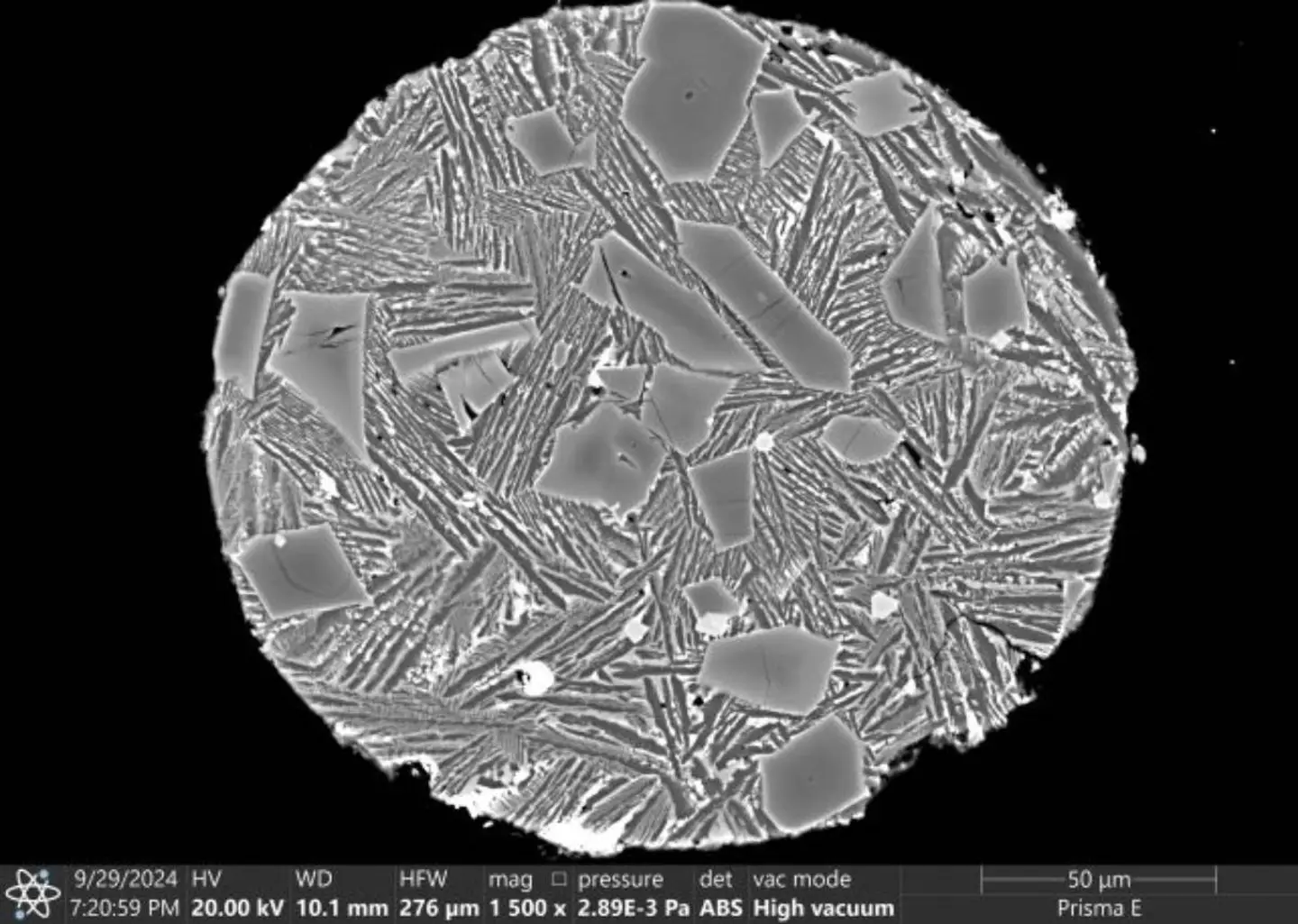

Microscopy and spectrometry techniques detected unusually high levels of isotopes in samples of olivine. This is a common silicate mineral that's typically found in volcanic rock and meteorites.

Importantly, the samples imply that these asteroids are far more common in striking the Moon than we originally thought.

The findings also back up the idea that such asteroids are far more common on the Moon than previously estimated, accounting for as much as 30 percent of the samples collected by Chang’e-6.

Co-author and Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry researcher Lin Mang suggests there could be massive implications for how we understand water arrived on the surface of the Moon and was distributed.